Issued by the Catholic Center for Studies and Media - Jordan. Editor-in-chief Fr. Rif'at Bader - موقع أبونا abouna.org

After the martyrdom of Bishop Epifanio (Epiphanius), assassinated in the convent of Saint Macarius, the Coptic Orthodox Church establishes 12 rules to guard monastic life in its traditional trait: a condition of seclusion from the worldly frenzy. One month to shut down their social media accounts.

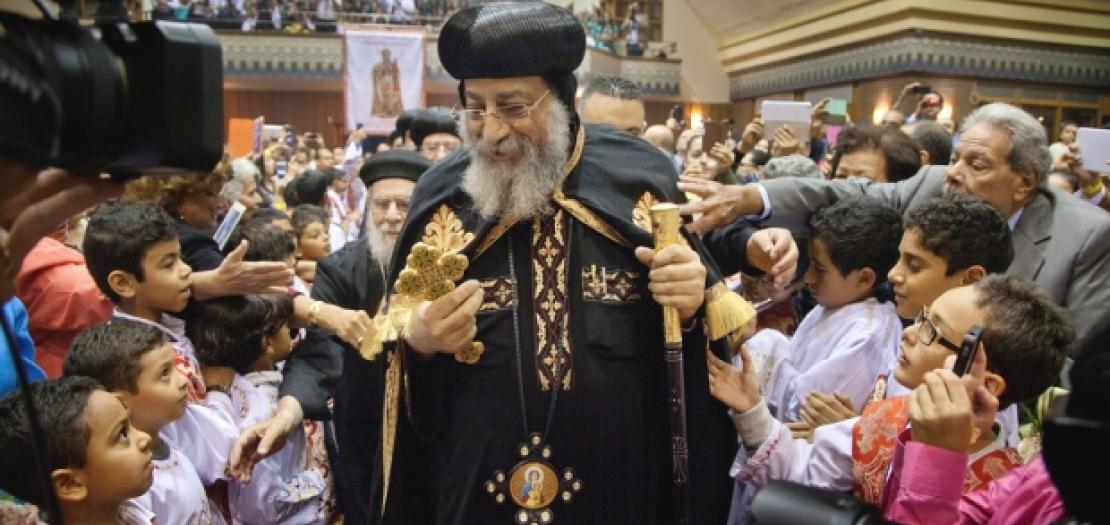

Monks and nuns of the Coptic Orthodox Church, no one excluded, have a month to shut down their personal accounts and any blog they manage on social media, such as Facebook and Twitter. Within that time frame, they will have to take leave of the forms of communication considered unsuitable for monastic life. Any failure to comply will result in canonical penalties. Among the 12 rules ratified by the patriarch Tawadros II, this is the decree that more than others will raise a clamour. The regulations were ordered for all those who live in the monastic condition inside the Coptic Orthodox Church, after the recent assassination of Bishop Epifanio, massacred – probably by stabbing – in the monastery of Saint Macarius, of which he was abbot .

The violent death of Anba Epifanio suddenly sped up the process of profound rethinking of the monastic life already begun in the Coptic Church by Pope Tawadros. The martyrdom of the bishop abbot is not due to some jihadist cutthroats. This time, his executioner probably belongs to the circle of people who live in the monastery or who habitually frequent it.

In recent decades, the rebirth of Coptic monastic life has been for millions of Egyptians the instrument to rediscover the treasure of the Christian faith, guarded over the centuries of Muslim domination. But different factors and even struggles and oppositions within the Church, risk dissipating so much spiritual wealth and fruitfulness, as often happens in ecclesial and clerical apparatuses, led by apathy to conceal their dependence on grace and to fall into forms of self-referential arrogance.

The 12 new provisions for the Coptic monks were formulated by the Committee for Monasteries and the Monastic Life of the Holy Coptic Synod, convened by Tawadros. 19 bishops and heads of monasteries took part to the assembly. The measures aim to guard monastic life in its traditional trait: a condition of seclusion from the worldly frenzy, marked by moments of prayer, work and silence. This is why the monks are also asked to withdraw from social media, which in the Coptic Church have often become an instrument to spread “confused ideas” and foster personal polemics and pseudo-doctrinal disputes.

Among other regulations, there are the order to suspend the acceptance of new candidates for monastic life for a year, and the halt of the priestly ordinations of the monks for three years. Other provisions include the stop to the creation of new non-authorized monastic communities; a stricter regulation of the access times of visitors and pilgrims to the monasteries, taking into account the days of fasting, prayer and silence that mark the monastic life; the prohibition to individual monks and nuns of receiving donations from the faithful – which can only be collected by the abbot or abbess of the monastery – and to get involved in economic projects and tasks that they have not been assigned by their community and by their superiors; the rule that even the exits and periods spent outside the monastery must always be authorized by those who lead the monastic community. Rules are also set to determine the maximum number of monks or nuns admitted to each individual monastery, to ensure an orderly and peaceful coexistence within each community.

After the provisions ratified by the patriarch, also other members of the Coptic hierarchy – like Bishop Raphael – have announced the closure of their personal online accounts and blogs, confirming that from now on, it will be possible to communicate with them only through traditional communication systems, such as the phone.

The restraint on the online presence of the Coptic monks and nuns is obviously linked to the emergency context in which the monastic life of the Coptic Church was thrown after the murder of Anba Epifanio. But it also reveals a certain affinity with the growing alarms regarding the effects of social media on the ordinariness of ecclesial life, felt within different Christian communities. While in the West the rhetoric of evangelisation via the Internet continues to be popular, the Maronite Church has released a magisterial document in February to try to stem the spread of online ecclesiastical brawls and fury on doctrinal issues, which intrigue mainly priests, devotees, self-proclaimed experts and “insiders”, gurus and small keyboard inquisitors.

The phenomenon of distorted Christian words in online para-doctrinal fights has recently also drawn the pastoral concern of Pope Francis: “Christians too – the Bishop of Rome writes in the Gaudete et Exsultate, the apostolic exhortation signed by him last March 19 – can be caught up in networks of verbal violence through the internet and the various forums of digital communication. Even in Catholic media, limits can be overstepped, defamation and slander can become commonplace, and all ethical standards and respect for the good name of others can be abandoned. The result is a dangerous dichotomy, since things can be said there that would be unacceptable in public discourse, and people look to compensate for their own discontent by lashing out at others. It is striking that at times, in claiming to uphold the other commandments, they completely ignore the eighth: ‘You shall not bear false witness’, and ruthlessly vilify others”.