Issued by the Catholic Center for Studies and Media - Jordan. Editor-in-chief Fr. Rif'at Bader - موقع أبونا abouna.org

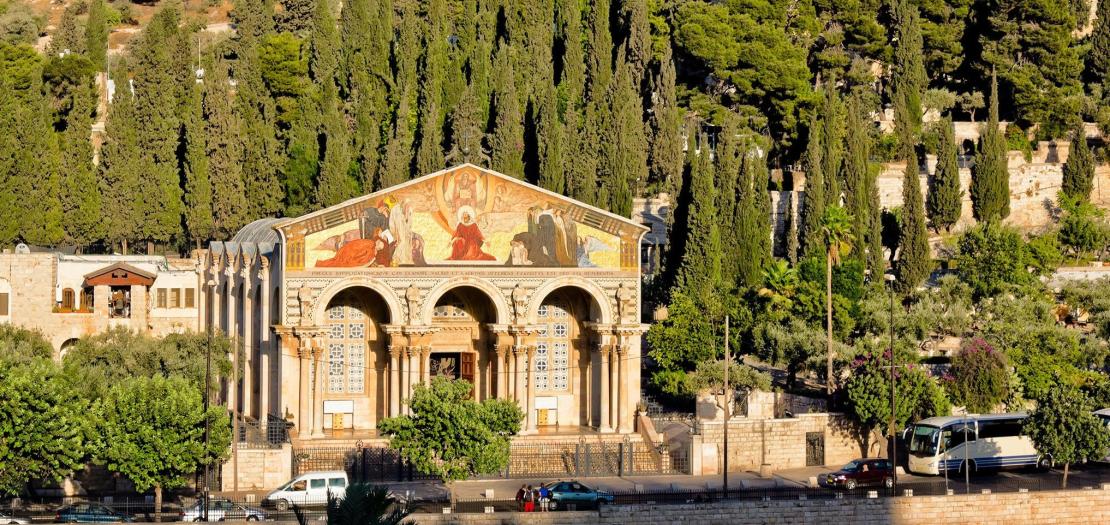

The Church of All Nations rises above the olive trees of the Garden of Gethsemane. Contained within is the rock upon which Jesus prayed and bled in agony as He consented to the Father’s will to make the supreme sacrifice of His life for the salvation of the world. The majestic basilica built over this hallowed place was consecrated 100 years ago, on June 15, 1924. This centenary provides a good occasion to explore this revered destination for pilgrims to the Holy Land.

The descriptions of the gospels align well with the location of the basilica at the northern foot of Jerusalem’s Mt. of Olives. St. John writes: “When Jesus had spoken these words, he went out with his disciples across the Kidron Valley, where there was a garden…” (John 18:1) St. Luke also indicates the location: “And he came out and went, as was his custom, to the Mount of Olives, and the disciples followed him.” (Luke 22: 39) St. Matthew connects the garden with the Mt. of Olives, writing: “And when they had sung a hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives.” (Matthew 26:30); “Then Jesus went with them to a place called Gethsemane…” (Matthewt 26:36)

According to the historian Eusebius writing in 330, the Christians of that time still had a vivid memory of the place where Jesus prayed in agony. Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, a Dominican priest and celebrated archaeologist of the Holy Land, says the site “has a strong claim to authenticity.”

Before you enter the Church of All Nations, you must first pass through the famous garden of olive trees. This area is worth exploring just as much as the basilica.

The Franciscans were able to gain possession of the grove in 1666 along with the ruins of the ancient church built on this site. In his Guide to the Holy Land, the Franciscan priest Eugene Hoade, recounts:

For a long time they left it in the state some pilgrims would like to see it still, an olive grove surrounded by a dry stone wall and a cactus hedge. But in 1848 they were obliged to enclose it to safeguard the property.

Ten gnarled olive trees are enclosed within this garden by an iron railing just outside the modern church built at the site of the agony. Eight of these are ancient and venerated as those beneath which Jesus prayed after the Last Supper and before His arrest. The other two were planted by Pope Saint Paul VI on his pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1964, and Pope Francis on his pilgrimage there in 2014. The saplings planted by the popes were grown from a cutting from among the eight very old trees in the garden ensuring the integrity and continuity of the garden’s genetic heritage.

There has long been debate over how old these original eight trees are. Botanists have claimed they can be as ancient as three thousand years, making them very likely the ones Jesus prayed beneath on Holy Thursday night. It has also been speculated that the likely fate of these first-century trees, however, was that they were cut down by the Roman armies in need of timber for their siege of Jerusalem in the year 70.

Recent scientific studies have brought further clarity. In 2012 the Italian National Research Council published its report after an intensive study declaring these trees to be from the 12th century—which seems exactly right as this is when the Crusaders built a basilica and renovated the garden on this site after they captured Jerusalem. This dating only refers to the trunk that is above ground and the foliage of the tree. The same research reveals roots beneath the ground to be more ancient. Even more compelling is how the study shows that the eight trees have an identical genetic profile which means the Crusaders rearranged the garden in the twelfth century by planting cuttings from the same, and older, “father” tree. It can be speculated that the Crusaders chose this tree for some special reason. Perhaps the locals knew it to be very old and that it was always considered to be from the time of the Lord in the first century?

The roots beneath the ground of these trees very likely link us to Jesus’ time, making these trees silent witnesses to the first moments of the Passion.

The Franciscans maintain this garden well. A great variety of flowers bloom among the olive trees. Leaves from these trees make popular souvenirs for the pilgrims. Some have criticized the appearance of the garden as not befitting the place where the Lord’s Passion began. They think it should be more solemn and austere. In reply to this criticism of the garden, G.K. Chesterton wrote: “The Franciscans have not dared to be reverent; they have only dared to be cheerful.”

Looming over the garden is the Church of All Nations. This grand monument is the third to have been built on the site. The first was erected during the reign of the Christian Emperor Theodosius who ruled Rome from the new capital of Constantinople in the east from 379-95. This Byzantine structure was built over the very rock at the foot of the Mt. of Olives which the earliest Judeo-Christians venerated as the spot where the Lord prayed and bled upon in agony. The altar of this ancient church was situated directly behind this rock making it the structure’s focal point. The late fourth-century pilgrim to the Holy Land, Egeria, refers to this as an “elegant church.” The last pilgrim to mention it in writings that have been preserved was Willibald in 724-25. This Byzantine church was likely damaged if not completely destroyed by the Persian sacking of the Holy City in 614. What was left is what Willibald saw. These meager remains were destroyed in an earthquake some twenty years later.8

When the Crusaders took the Holy Land, they built a small oratory at first, and they expanded it into a much larger church which they named St. Savior. This church was given a different orientation than the original Byzantine structure. Apparently, the Crusaders wanted the rock where Jesus knelt to pray to be included in three different apses to symbolize His triple prayer while in the Garden: “So, leaving them again, he went away and prayed for the third time…” (Matthew 26:44) Murphy-O’Connor, wryly calls this “a rather material interpretation of the triple prayer of Christ.” The fate of this Crusader church is unknown. There is evidence that it was still functioning in 1323 but the site was clearly abandoned by 1345.

The reconstruction of this sanctuary was preceded by archaeological excavations which began in 1891 and continued to 1909. This work brought to light the Crusader church of St. Savior and even more valuable, the remains of the Theodosian church which can be seen today through the floor of the present church built on the site.10 The construction of the Church of All Nations began in 1919 and was consecrated on June 15, 1924. It is more formally called the Basilica of the Agony but most refer to it as the Church of All Nations. The coats of arms of many countries appear throughout the church, especially the ceiling, as a sign that it was built through the generosity of Christians everywhere which is why it is aptly given this name.

Its building was committed by the Franciscans to Antonio Barluzzi (1884-1960), who is remembered by history as the “architect of the Holy Land.” He designed this shrine along with others such as those in Bethpage, Bethany, the Mt. of Beatitudes, and other smaller chapels within larger shrines including the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. His greatest achievements are usually considered to be the Church of All Nations as well as the Church of the Transfiguration that sits atop Mt. Tabor. Both are celebrating their centenary this year.

The facade of the Church of all Nations is magnificent and is typical of a Roman basilica. The four sets of supporting Corinthian columns are each topped with a statue of one of the evangelists holding an open book with an inscription. The book held by St. Luke gives attention to the rock inside having been sanctified by receiving droplets of the Lord’s Precious Blood: “Et factus est sudor ejus sicut guttæ sanguinis decurrentis in terram, And being in an agony he prayed more earnestly; and his sweat became like great drops of blood falling down to the ground.” (Luke 22:44)

The triangular pediment above the colonnade is a gorgeous and colorful mosaic depicting Christ as the mediator between God and men. The Savior is depicted in the bottom center in prayerful agony. To His left are a throng of the suffering poor and lowly and to His right are gathered the rich and powerful who amid their own suffering acknowledge that all their earthly glory is mere dust. Both groups look to Christ with confidence. An angel is shown receiving the Heart of Jesus to present it to God the Father Who is above, seated in glory. This mosaic summarizes all that takes place in the Lord’s Passion which began in this holy place— Christ as Mediator, offers His own suffering and those of the world to the Father. This striking scene is explained in the inscription just below it in words taken from St. Paul: “…preces, supplicationesque…cum clamore valido, et lacrimis offerens, exauditus est pro sua reverential, “[He] offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears…and he was heard because of his reverence.” (Hebrews 5:7)

The facade is surmounted by a central cross with two stags on each side looking up to it recalling the words of the psalmist King David: “As a deer pants for flowing streams, so pants my soul for you, O God.” (Psalm 42:1)

The facade of the church is Romanesque in style, but the body of the church is more Eastern in character. The roof is made up of twelve small domes. The interior ceiling recreates the star-studded night sky under which the Lord prayed in this place through a dark blue mosaic. The whole church evokes the darkness of the night in which Jesus agonized in prayer. Natural light only subtly skirts through the violet-blue alabaster windows. The somber atmosphere of the darkness befits the sorrowful nature of the site where Christ’s Passion began.

In each of the three apses in the front of the church are large mosaics depicting the kiss of Judas to the left, Christ in agony while being consoled by the angel in the center, and Jesus’ arrest to the right. The central mosaic depicts Christ praying in agony upon a rock—looking down from the mosaic the very rock upon which the bloody sweat of the Savior is beheld just before the altar. The rock is encircled with a silver ornamentation depicting the crown of thorns.

The desire of every pilgrim to this place is to kneel here and pray upon the same rock as Jesus did in agony.

Here He prayed, “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me,nevertheless, not my will, but yours, be done.” (Luke 22:42)

In a different garden, the Garden of Eden, our first father, Adam, did not follow God’s will but his own. He gave in to the temptation of the demons and ate the forbidden fruit bringing about the Fall of man. In the Garden of Gethsemane, the process of reversing Adam’s sin began. At the outset of His Passion, Jesus resisted the temptation to follow the fearful will of His human nature. He instead followed that of His divine nature, and rather than fleeing, gave Himself up to arrest and crucifixion. As St. Paul teaches: “For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive.” (1 Coronthians 15:22)

Perhaps the greatest grace that can come to a pilgrim from praying in this holy place is to leave with an ever-firmer resolve to conform his will to God’s. Fiat voluntas tua!