Issued by the Catholic Center for Studies and Media - Jordan. Editor-in-chief Fr. Rif'at Bader - موقع أبونا abouna.org

Despite its historical importance, much of Abila remains vulnerable today

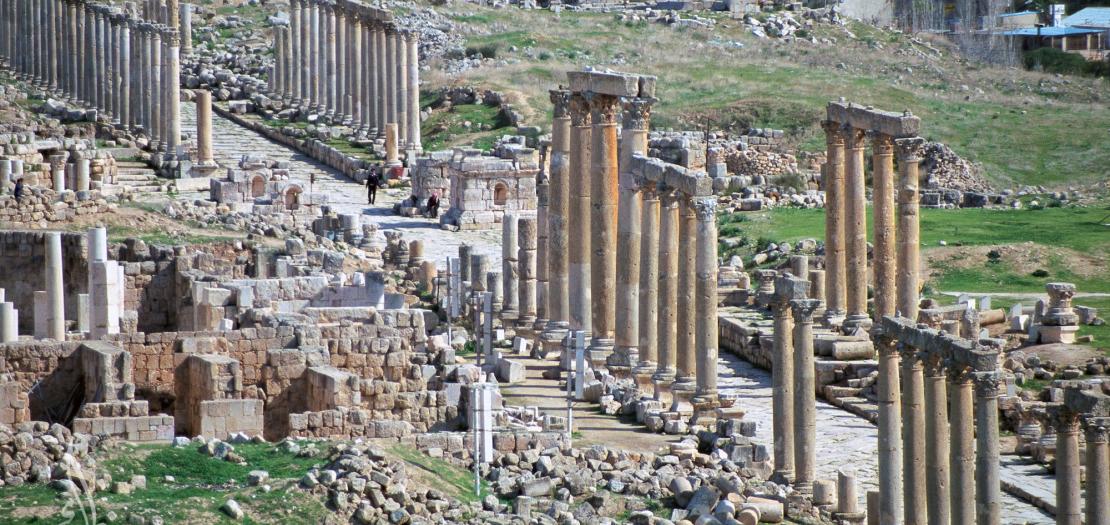

Located in a fertile valley northeast of Irbid, Abila secured its place among the ten cities of the Roman Decapolis through its strategic location, thriving economy, and distinct identity — so much so that it minted its own coins under the name Seleucia Abila.

Despite this rich legacy, much of the city lies hidden beneath the earth today, overlooked and missing from Jordan’s official tourism map.

Beneath the surface lie richly painted tombs; above ground, the remains of Roman baths and Byzantine churches dot the hills. An elaborate water system — including 15 kilometers of underground tunnels — once sustained the city’s population, estimated at 15,000 inhabitants.

Yet today, visitors encounter no signage, minimal protection, and little explanation of the site’s remarkable past.

“The site is not yet fully prepared to receive visitors and has not been officially included on the national tourism map,” the Department of Antiquities told The Jordan Times.

Abila’s history stretches back to the Bronze Age, approximately 6,000 years ago. It remained occupied nearly continuously until the Mamluk period around 1500 AD, making it one of Jordan’s longest-inhabited sites.

Archaeological evidence reveals the city’s peak during the Greco-Roman and Byzantine periods, when it became a prosperous hub in the Decapolis, a federation of ten Greco-Roman cities protecting the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire.

Excavations led by archaeologists from John Brown University since 1980 have uncovered Byzantine churches, a Roman bath complex, a theatre, city gates, a monastic complex from the Early Islamic period, and miles of water tunnels connecting springs and cisterns.

Research show that the city remained active well into the early Islamic period, long after earlier scholars had assumed northern Jordan was abandoned.

Yet, despite its historical importance, much of Abila remains vulnerable today.

Some of its most significant underground tombs have been looted, even after excavation. In certain areas, repairs used inappropriate materials, and many parts of the site are exposed to erosion, weathering, and human damage.

“The site is monitored around the clock by guards; however, due to its large size, vast spread, challenging terrain, and lack of a camera surveillance system, some violations may still occur by individuals who are not committed to preserving the site’s cultural heritage,” the Department explained.

Partial fencing has been installed, but full protection has been delayed due to land ownership issues.

“Some landmarks within the site have already been fenced, but the fencing has not been completed due to the ongoing procedures for the expropriation of the site.”

In 2023, restoration work was carried out on a church apse, and the Department has begun laying paths to improve visitor access.

“Annual maintenance and restoration plans are implemented for the site. Rehabilitation and restoration works are carried out on the excavated areas either preventively or permanently. The most recent work was the restoration of the apse in 2023, in addition to initiating the development of pathways within the site.”

However, the lack of completed excavations and scientific documentation has hindered efforts to promote the site to visitors, limiting signage, guides, and interpretive materials.

“The reason is that archaeological excavations and scientific documentation of the site are not yet complete. As a result, the final verified information may still be incomplete and subject to change based on ongoing discoveries and new studies,” the Department of Antiquities explained.

The absence of visibility and funding has placed the site at a disadvantage compared to other Decapolis cities.

“The biggest obstacle to implementing maintenance and restoration projects at the site is the lack of financial resources dedicated to such sites.”

Today, Abila sits in relative isolation, overshadowed by better-known neighbors like Umm Qais and Jerash.

But the city’s legacy as a “city of asylum,” a place of refuge protected by sacred law, remains visible in its coins and surviving architecture. It was a center of agriculture, craftsmanship, and religious life – a testament to a community that thrived across millennia.

“The Department of Antiquities always welcomes the participation of any community group or educational institution that contributes to the preservation of the site and promotes awareness of its cultural value — this applies to Abila and all other archaeological sites.”

Abila remains one of Jordan’s most promising but under-supported archaeological sites. Its layered history — from the Bronze Age to the early Islamic period — is still being revealed, slowly and carefully, by teams of researchers.