Issued by the Catholic Center for Studies and Media - Jordan. Editor-in-chief Fr. Rif'at Bader - موقع أبونا abouna.org

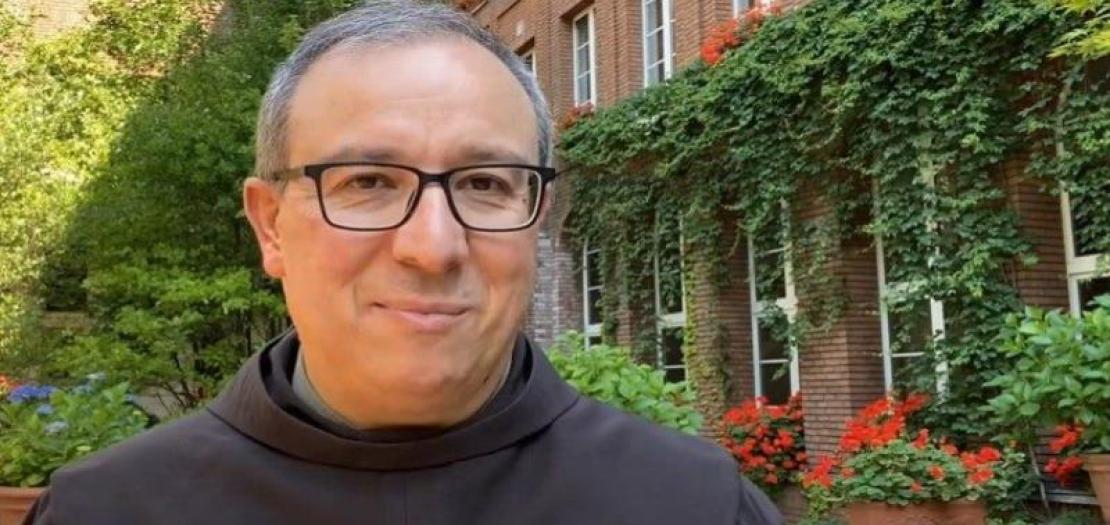

We met Br. Francesco Ielpo, appointed Custos of the Holy Land by His Holiness Pope Leo XIV on Tuesday, June 24.

We reach him by phone, still immersed in his responsibilities as General Visitor of the Franciscan Provinces of Campania, Basilicata, and Calabria, before he begins his full-time service as Custos of the Holy Land in the coming days.

Br. Francesco, what does it mean to be a Franciscan today?

I answer as St. Francis did: when asked this question, he described the characteristics of ten different friars. It’s as if he were saying that the true Minor Friar today is a fraternity, and that only a fraternity can fully embody the Franciscan charism.

“Fraternity” is a word that is very dear to me. Being a Franciscan today in the Holy Land first and foremost means being fraternity within the Custody: this is the primary proclamation, as St. Francis hands down to us in the Earlier Rule, Chapter XVI.

In these first days, I am realizing how much emphasis there is on the appointment of the new Custos of the Holy Land. But I am a human being, a person with limits and fragilities, with miseries, who is simply trying to respond to his vocation.

Moreover, our Franciscan mission is not embodied in the figure of the Custos alone, but is carried out by over 200 friars who daily sacrifice themselves, give their lives, and carry out our mission with dedication, in silence, and sometimes in hiddenness.

So… it is a “fraternity” that keeps the Custody of the Holy Land alive.

What does “to guard” mean today for a Franciscan?

It’s a verb that has deeply challenged me during these years of service as Commissary and then as Delegate of the Custos.

“To guard” is an important verb, even from a biblical point of view, and the first parallel that comes to mind is the way St. Joseph guarded the Holy Family.

I believe the model we should be inspired by is precisely St. Joseph, who is called to guard something that is not his, something he did not generate. And yet, he is called to give his life, to guard, to protect, to help grow, to love the most precious thing—the child Jesus and His Mother—who are not his.

It means giving your life completely for something that is not yours, that does not belong to you, but has been placed in your hands.

Then there is a second aspect connected to the verb "to guard": I feel strongly called to guard my vocation, and the vocation of the friars. Beyond guarding the holy places and the living stones who dwell there, without guarding our vocation, even our service would lose meaning and purpose.

What are the most important challenges to face for the Franciscan presence in the Holy Land?

I have only just landed in this role, and if I have to respond immediately, without too much reflection, I would say that I would like to grasp and read the most urgent challenges together with the friars who have lived in that land for many years and who have personally experienced these difficult and dramatic times.

The first challenge is to enter with great humility and to discern together, to read the signs of the times together to understand what the Lord is primarily asking of us right now.

So there is a challenge of synodality among us, which also becomes a first testimony, and then solidarity with the faithful and with the peoples.

Then there is certainly the challenge of peace—of being a peaceful and peace-making presence, humble and silent, which nonetheless communicates a different way of living and being in conflict.

There is the emergency of charity, of the material needs of the people.

There is a great educational challenge to which the Custody has always been called.

It will be essential to begin with a shared reading, rather than assuming we already know what the priorities are.

From your previous life and experiences as a Minor Friar, what background do you bring to the role you are about to begin as Custos?

Retracing my vocation chronologically and recalling what obedience has asked of me, I am definitely indebted to my story.

I bring with me an important background from my years of teaching, my contact with young people and with the world of education.

There I learned that whatever you propose—whether pastoral or social—must always have a pedagogical intention, a formative purpose.

In my experience as a parish priest, I learned to love the Church. When I first became a parish priest, I told myself that even though I had studied theology and worked in education, I did not yet have a clear vision of the Church.

I learned that we must always ask ourselves what idea of Church we have, what idea of the people of God, of community, and how we fit into it.

My service in the Custody was unexpected. I asked twice for the possibility to leave as a missionary to Africa. In 2013 I was ready to go, but at the same time, I was offered the position of Commissary for the Holy Land in Lombardy.

I had never thought about it and never desired to work for the Holy Land… I accepted the proposal to become Commissary because I start from the idea that what is proposed to me is always better than what I have in mind.

And so I discovered the world of the Holy Land, the Custody, the friars.

And what did it teach me? The greatest lesson in my personal and Franciscan life was to fall in love with Jesus again, to fall in love with the Gospel and especially with the humanity of Christ.

The Holy Land taught me that the Word became flesh, that it is a real, concrete presence—that He cried in that cradle, got dirty, that Mary changed His diapers, as is sung in a hymn during the midday procession in Bethlehem.

It was an experience that broadened my horizons, opened me to the international, intercultural community.

Especially in these years spent in Rome.

At the table, I’m the only Italian. I look at the faces of these brothers of different nationalities—China, the United States, Poland, Peru, Vietnam, and others… I look at them and realize that what unites us is that we were all called by the same Lord and that we all profess the same Franciscan Rule: that is the essence of our life!

In this world torn apart by war, what message can St. Francis of Assisi and his followers bring?

I am aware that it’s one thing to say something in words, and another to live it in daily life.

When you’re in difficulty, when you’re under bombs, when you see injustice, when your heart breaks at seeing starving children, when you witness the atrocities committed by terrorists…

Even so, we are called to guard (this word returns again!) a heart capable of seeing reality as Christ sees it—and therefore without enemies.

And that’s not easy!

Without taking sides, but with a heart that never gives up on the idea that you can be my brother, that I can engage in dialogue with you.

There must be a possibility for everyone!

And as I say this, I realize that these may sound like beautiful theoretical words, but day-to-day life is another matter.

We must help each other to cultivate this vision, the one St. Francis had when he stood before the Sultan, or before the cardinal delegate from whom he asked permission to leave the camp.

A disarming gaze, because it was concerned for the good of the other, for the salvation of the other—even of the one who at that moment seemed to be the enemy.

Are there any key words you would like to make your own and address to the friars and to those who love the Holy Land?

I make my own the words of the Franciscan tradition and of the friars’ presence in the Holy Land:

brothers and minors, to be witnesses of dialogue and peace.

And to conclude, I want to invite everyone never to forget to pray and to beg for peace—not only for the Holy Land but for the more than 50 conflicts currently taking place around the world.