Issued by the Catholic Center for Studies and Media - Jordan. Editor-in-chief Fr. Rif'at Bader - موقع أبونا abouna.org

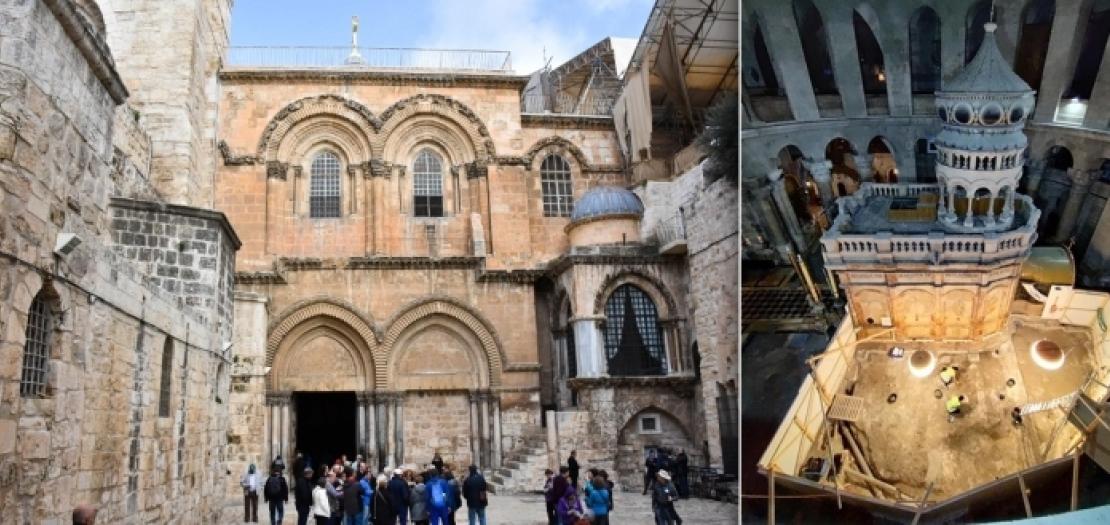

Beneath the incense-filled vaults of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, one of the most intricate and profound archaeological operations in the Holy Land is unfolding. What began in 2022 as a restoration project for the church’s deteriorating floor has become a journey into the deep layers of sacred history. Led by Prof. Francesca Romana Stasolla of Sapienza University of Rome, and coordinated by the three main Christian communities— the Franciscans (Custody of the Holy Land), the Greek Orthodox, and the Armenians—in collaboration with the Antiquities Authority, this project seeks to preserve the past while protecting the present.

Restoration That Sparked Revelation

The current archaeological project stems from urgent conservation work launched in 2016, when engineers detected alarming signs of structural degradation in both the Edicule (the Tomb of Christ) and the church as a whole—including the flooring, plumbing, and ventilation systems. The urgency was both spiritual and structural.

In a historic event during that early phase, the original burial slab of Christ was uncovered for the first time in over 500 years, a moment described by many as a rare intersection of faith and science. This moment rekindled global interest in the site and laid the groundwork for the broader archaeological campaign launched in 2022.

To allow ongoing worship and pilgrimage, the restoration was divided into 11 zones within the basilica. Excavation proceeds around the clock in shifts, pausing during major liturgical events like Holy Week and Easter.

From Quarry to Tomb: A Sacred Timeline Beneath the Floor

Accompanied by visitors and journalists, Prof. Stasolla guided tours down to one of the deepest excavation areas, nearly six meters below the surface. “This zone offers a remarkably compressed historical sequence,” she explains.

Archaeologists discovered that the site once functioned as an active quarry in the Iron Age, used for cutting limestone. As quarrying ceased, the area was gradually filled in and converted into an agricultural garden, with olive trees and grapevines—a transformation confirmed by archaeobotanical evidence, including ancient olive pits, grape seeds, pollen, and animal bones. These findings echo the Gospel of John’s description: “In the place where He was crucified, there was a garden.” (John 19:41).

Stasolla emphasizes, “Analysis isn’t limited to stone remains. We’re also studying sediments, pollen, and botanical layers, to reconstruct the environmental and human activity that once animated this part of Jerusalem.”

Golgotha Endures: Stones of Memory

Father Amadeo Ricco, an archaeologist at the Franciscan Biblical Institute, draws attention to a five-meter rocky outcrop of Golgotha still visible today. This formation—central to Christian memory as the hill of the Crucifixion—was preserved even after Emperor Hadrian erected a pagan temple over it in the 2nd century A.D., in an attempt to erase Christian presence.

“Ancient Latin and Greek sources confirm that early Christians continued to venerate this location, even during persecution,” says Fr. Ricco. “Memory and faith endured.”

What the Gospels Didn’t Say

Beyond confirming biblical texts, the excavations add new depth. Archaeologists identified multiple rock-cut tombs outside Jerusalem’s ancient walls, including one that may be the donated tomb of Joseph of Arimathea, the wealthy council member who offered his own unused grave for Jesus.

Fr. Ricco notes, “Everything seems to have been providentially prepared for Jesus to be buried with dignity, despite the haste and horror of those days.”

From Ruin to Resurrection: Hadrian, Constantine, and the Church

After Hadrian’s attempt to erase Christian memory by covering the site with pagan temples, Emperor Constantine restored the sacred geography in the 4th century. At the urging of his mother St. Helena, the Roman emperor ordered the demolition of Hadrian’s shrines and began construction of a monumental church over Christ’s tomb around 326 A.D., using recycled Roman masonry. The construction took nearly a decade.

Though parts of the church were destroyed during the Persian invasion (614 A.D.) and again by the Fatimids (1009 A.D.), the Crusaders rebuilt the complex in the 12th century. Many of the Holy Sepulchre’s current features—including the Rotunda, Golgotha chapel, and Stone of Anointing—stem from this era.

Recent excavations unearthed technical insights into Constantine’s builders, especially in the north aisle. Archaeologists retraced trenches dug by Fr. Virgilio Corbo in the 1960s, confirming earlier research and adding new data. They found that the bedrock quarry had uneven, deep-cut surfaces, requiring early Christians to level the terrain using soil and ceramic-rich fill layers—a primitive yet ingenious engineering technique. The team also studied the foundation methods of the Constantinian northern wall, which remains partially intact.

Archaeology in the Presence of Prayer

Despite the complexity of the work, prayers and liturgies have never stopped. Excavations pause during feast days and continue in harmony with the sacred rhythm of the site. “Archaeology has illuminated realities we didn’t know,” says Fr. Ricco, “but more than that, it has deepened the reverence we already had.”

Conclusion: A Living Jerusalem

What’s being uncovered in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is far more than ancient debris. These stones speak of resurrection, of memory carved in limestone, of faith that survived suppression, and of a sacred landscape still alive with meaning.

The Church, once a quarry, garden, and tomb, remains a living symbol of hope—a place where stones testify, and where the silence of centuries gives way to voices of prayer and discovery.